50 local residents report burns and skin lesions after wastewater spill and oil pipe leak

Glencore ignored reports of serious injuries to local residents in Chad living near its Badila oilfield following a September 2018 wastewater spill and oil pipe leak, a new report published today reveals. The Badila oilfield is operated by PetroChad Mangara Ltd, a 100%-owned subsidiary of Glencore Plc, one of the largest natural resource companies in the world.

The report by corporate watchdog, RAID, describes the collapse on 10 September 2018 of a basin holding produced water, a by-product of crude oil production. The wastewater poured into the local Nya Pende River, crucial for the daily life of thousands of local residents. Two weeks later the situation was aggravated further when local residents noticed a crude oil leak from Glencore’s oil feeder pipe near to the river.

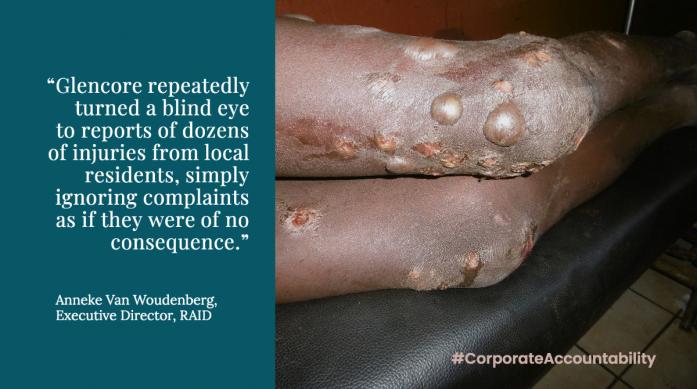

RAID conducted an 11-day field mission to the villages near the Badila oilfield in June 2019 and interviewed 116 people. At least 50 local residents, many of who were children, said they suffered burns, skin lesions, and pustules after bathing in the water in the days and weeks that followed. Others reported blurred vision, stomach aches, vomiting and diarrhoea after using the water. Some required hospitalisation, including at least 2 children. Local residents noticed fish floating dead and said dozens of livestock died suddenly after drinking the river water.

“Glencore repeatedly turned a blind eye to reports of dozens of injuries from local residents, simply ignoring the complaints as if they were of no consequence,” said Anneke Van Woudenberg, the Executive Director of RAID. “Local people believe toxic substances after the spill and/or the oil pipe leak are responsible, but 16 months later Glencore still hasn’t concluded a thorough and independent investigation.”

According to residents, Glencore’s wastewater basin had been leaking weeks before it collapsed, but the company failed to properly address the problem. Glencore unsuccessfully sought to persuade local chiefs and the Chadian government to allow a controlled release, but it provided no proof the wastewater was harmless and its request was refused.

One of those most seriously injured was a 13-year-old boy, Jean (not his real name), from Karwa village, who went to bathe in the river downstream of the spill and the reported oil leak. He remembered noticing oil on the surface of the water. Soon after he finished bathing, his skin began to burn and pustules appeared all over his body. Around the same time, Paul (not his real name), aged 11 or 12, was watering his cattle at the river. He squatted down in the water and splashed his face to cool himself. His skin began to burn and pustules appeared on his ankles, hands and face. Some of the cattle who drank the water also later died.

Both boys ended up in hospital. Jean, in intense pain, was taken by his family to a local doctor who said “the wounds are because of crude oil.” He urged the family to take Jean to a hospital in Moundou, some 50 kilometers away. But the hospital was unable to adequately treat Jean and recommended specialist care in Cameroon, which his family could not afford. Paul was also seen at Moundou hospital. A family member told RAID the doctor said Paul’s injuries were due to washing in “bad water” which contained hydrocarbons.

When RAID met Jean and Paul in June 2019 their scars were still visible. Jean was withdrawn and said he continued to suffer. He described the events as “the most painful of his life.”

Glencore was alerted to these and other injuries. A Glencore team visited Jean at his home and took photos of his injuries but conducted no further evaluation and did not formally record a complaint. Glencore later said that Jean suffered from “a condition commonly seen during the rainy season” though it did not identify the condition.

In Paul’s case, a two-page report by Glencore staff concluded his injuries were inconsistent with his account and were not caused by any of Glencore’s activities as they believed the boy had bathed in a location upstream of the company’s operations. Paul and his family did not see the report nor were they provided an opportunity to comment on it.

Glencore refutes that the spill posed a health risk and said the wastewater from the basin was predominately rainwater. In written correspondence with RAID and in an October 2019 meeting, the company said it based this conclusion on a sample taken from the basin on the day of the spill, which “was found to be within the limits required by the International Finance Corporation’s performance standards.” But RAID challenged this finding as some of the results showed levels that exceeded these standards and more than half of IFC’s criteria were not tested. Glencore did not share these and other test results with the local communities.

Glencore’s local employees received calls about the injuries and the death of livestock in the weeks after the wastewater spill, but did not pursue them believing the test showing the wastewater to be harmless. Glencore said it provided compensation in relation to 89 complaints relating to crop and tree damage caused by flood but that “of the complaints received … none related to injuries” and that therefore it “did not investigate complaints of this nature.”

On the oil pipeline leak reported in September 2018 by local residents and investigated at the time by a local civil society group, Glencore said it had no “recordable pipeline leaks” on 26 September 2018. It said there had been maintenance on the pipeline at a similar location on 16 and 17 August 2018 but that there had been no damage to the pipeline itself or any loss of hydrocarbon. It said it visited the area on 21 October 2019 which “confirmed there was no evidence of hydrocarbon release in the vicinity” though it provided no details on what, if any, tests had been conducted to confirm this conclusion.

Glencore stated “we continue to believe that the identified medical cases are unrelated to our operations, however, we are committed to trying to understand the root causes.” Glencore informed RAID that following its research, the company is reviewing its water sampling and testing protocols and that its grievance mechanism will undergo an internal audit. It also confirmed the appointment of an independent consultant to conduct an assessment on ground water, river water and soil samples around the Badila concession and the commissioning of an “independent Health Impact Risk Assessment.”

RAID welcomes these commitments and urges the company to publish all findings.

“Glencore failed the local Chadian community around its Badila oilfield at nearly every turn and should have conducted a full investigation into the harms as soon as local residents raised concerns,” Van Woudenberg said. “Glencore says it is committed to acting responsibly, but the manner in which it dealt with the spill and its after-effects raises serious questions and should spur governments into stronger regulation of companies so that fine words are followed by meaningful action.”

Additional Links:

For a full copy of the report click here

All correspondence between RAID and Glencore can be found here.

For additional RAID publications on Glencore:

Blog: Glencore growing legal troubles with Katanga Mining

Blog: Applause for SFO on Glencore probe, but what progress on ENRC?

Report : PR or Progress? Glencore Corporate Responsibility in the DRC (June 2014)

Follow RAID on Twitter at: @raidukorg or on Facebook